Every Guillermo Del Toro Movie Ranked Worst To Best | Screen Rant

Visionary director Guillermo del Toro has developed an incredibly nuanced filmography during his career—here's a look at how his movies rank against one another, from worst to best. While he has only directed ten movies, del Toro is easily one of the most beloved mainstream directors currently working in Hollywood. Thanks to his devotion to horror, science-fiction, and fantasy, his distinctive vision has seen him win over both audiences and critics alike.

Popular director Guillermo Del Toro finally won his long-awaited Best Director Oscar in 2018 for The Shape of Water, but long before that triumph, he had already made his mark. This has been deemed possible due to his ability to veer between low-budget independent films and mega-blockbusters, honing his skill with original stories and well-known intellectual properties alike. Across genres, themes, and stylistic approaches, the connective tissue between his movies is dense and fully realized.

It is interesting to delve deep into del Toro's narratives, owing to the fact that they are richly drawn, mixing the lushness of fairy-tales with the hallucinogenic madness of H.P. Lovecraft. To him, horror, sci-fi, and fantasy are explicitly political, the perfect mediums to explore the poisonous grip of unfettered power and the ghosts of history. His Hollywood fare is just as vibrant and densely layered as his Spanish-language efforts, and he hops between the two with ease. Here's how Guillermo del Toro's released movies rank, from worst to best.

After the success of his feature directorial debut, del Toro was lured to America by the now-infamous Weinstein brothers with the promise of a $30 million budget and the chance to adapt a short story by sci-fi author Donald A. Wollheim. Filming was notoriously fraught after Bob Weinstein insisted early footage of Mimic wasn't scary enough. After many fights, Weinstein even tried to get del Toro fired, prompting del Toro to say in an interview with Independent that making the film was "one of the worst experiences of my life [...] It was a horrible, horrible, horrible experience." He also disavowed the final cut of the movie until he was able to release a director's cut in 2011. Both versions of Mimic are interesting but extremely flawed. It's clear to see del Toro's struggle to combine his unique genre sensibilities within the confines of a studio picture intended for a mainstream audience.

Del Toro’s return to Hollywood following the mess of Mimic was a much more successful effort, and Blade II is now widely considered to be the best of the three Blade movies starring Wesley Snipes. Roger Ebert described the movie as a "vomitorium of viscera," which perfectly captures del Toro's mad scientist approach to monsters, gore, and vampire lore. Suitably for a sequel, Blade II is bigger, messier, and a lot weirder, although the script is weaker in terms of character and plot. Del Toro more than makes up for those failings with pure spectacle and was given the opportunity to show off what he could do when he was left to his own devices.

One of Guillermo del Toro's greatest assets is his long-running collaboration with actor Ron Perlman, the original Hellboy star. The pair have proven to be a perfect match for one another, with del Toro using Perlman's distinctive appearance and on-screen presence to its greatest advantage in 2004's Hellboy. Perlman is achingly perfect in the title role, not just physically, but through sheer force of gruff charm. Del Toro crafted a hugely enjoyable supernatural superhero movie around his performance. The movie takes the deliberately ludicrous story of mystical Nazis, demons from hell, and tentacled behemoths just seriously enough, with del Toro lavishing attention on every single creature. Nobody in Hollywood loves monsters as much as Guillermo del Toro. The biggest fault with Hellboy is the use of an audience avatar in the form of the dull human protagonist (cut from the sequel). The monsters are more exciting than the humans, and that's how del Toro likes it.

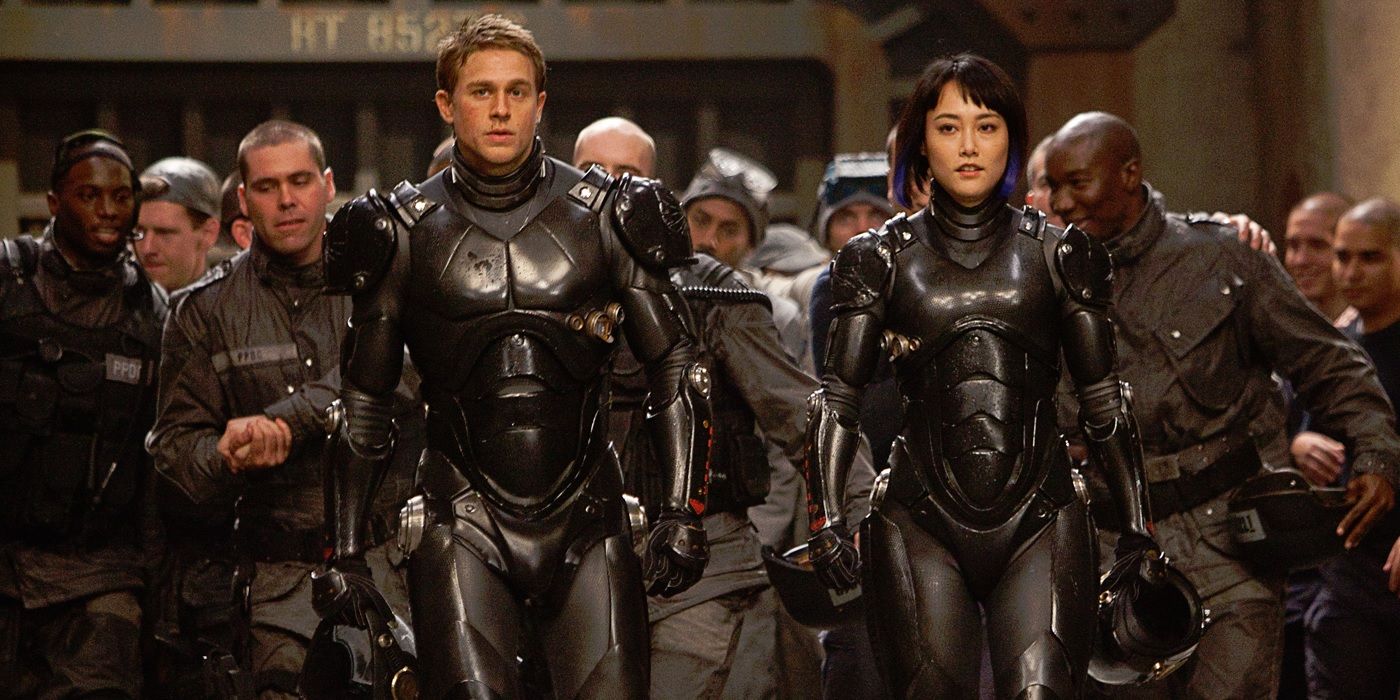

Fans of old-school Kaiju movies from Japanese cinema are exactly who del Toro made Pacific Rim for. With huge robots and monsters—and a budget to match—del Toro got to unleash his purest, most undiluted enjoyment of this sub-genre on the big-screen. Pacific Rim is a ridiculously enjoyable, high-concept spectacle that wears its heart on its sleeve and invites audiences to go along wholeheartedly with its silliness. It helps that del Toro can compose a monster mash punch-up as artfully as the genre has ever seen, and the acting ensemble—while mostly given broad archetypes to work with—are clearly having a blast with material that is bombastic and keeps just enough humanity to keep it afloat. Del Toro may have made better movies, but none are as unabashedly enjoyable as Pacific Rim.

When The Shape of Water won Academy Awards for both Best Director and Best Picture, many critics sneered that the Oscars had made yet another safe choice. It says a lot about del Toro’s work that his Cold War fantasy romance, wherein a woman falls in love with a fish-man, is considered one of his “safer” efforts. In many ways, that’s not a lie: The Shape of Water is as close as the director has ever gotten to making an old-school golden age Hollywood romance in the vein of Casablanca. Only del Toro could get an audience to invest so emotionally in whether or not Sally Hawkins’s introverted cleaner will save and have sex with an amphibious lifeform—and let viewers know exactly how such an act is biologically possible. This is del Toro at his sweetest, but he doesn’t dilute his dark side, as evidenced in the borderline-maniacal villain, who is played with typical intensity by Michael Shannon. This may be “safe” del Toro, but that doesn’t mean he’s still not risking it all.

Del Toro exploded onto the scene with his horror debut, which sharply reimagined the well-worn vampire mythos as a tale of technology, religious guilt, and familial trauma. In Cronos, a kindly elderly antique dealer is bitten by a mysterious clockwork scarab he discovers in the statue of an archangel. Contained within is an insect that grants him a new lease on life, but at the cost of an insatiable thirst for blood. It’s rare to see a wholly unique take on vampires in cinema, but Cronos brings a true freshness to the concept and uses it to explore the religiosity of Latin America with grace. While it's more restrained than del Toro's next few movies, the grandeur and frenzied mood the director would later make his patented style is apparent in moments such as the story's heart-wrenching climax.

Crimson Peak was disappointingly sunk at the box office by bad advertising that sold the movie as a classic horror movie rather than the luscious Gothic romance it really was. While there are chills and bloody scares a-plenty, the real genius of Crimson Peak is found in its melodrama, which blends together stories like Rebecca, The Castle of Otranto, and Dark Shadows. It's a visual marvel, especially through the mega-sleeved costumes and the eye-watering sight of the eponymous mansion. The cast is excellent, but Jessica Chastain’s performance as the sister consumed by lust and seething jealousy is one of the best of any del Toro movie. Crimson Peak is also a film utterly bereft of irony and cynicism. There’s no wink or nod at the theatrical nature of this tale. Del Toro has always been a deeply earnest filmmaker, and Crimson Peak succeeds largely because he refuses to weaken that aspect of his vision.

After the success of Hellboy—and following the victory lap of Pan’s Labyrinth—del Toro returned to the world of Mike Mignola’s comics, and was essentially given carte blanche to make whatever movie he wanted. In that sense, The Golden Army is to del Toro what Batman Returns is to Tim Burton: a comic book movie that is at its best when it’s an unashamed platform for its distinctive director to go wild. The sequel is more visually exciting, with moments such as a visit to the troll market and the death of a tree giant ranking high with some of del Toro’s best scenes in his directorial career.

There’s a much greater focus on the fantastical here, as well as the romantic elements, particularly with the relationship between Hellboy and Liz. The film even veers into slapstick and drunken rom-com sing-alongs, all of which fit surprisingly well among the movie's more traditional action beats. It’s a shame that del Toro never got to finish the Hellboy trilogy, and the failure of the more “adult” R-rated reboot only further proved that the director was perfect for this material in a way no other filmmaker could hope to replicate.

Del Toro's neo-noir psychological thriller, Nightmare Alley is based on the eponymous 1946 novel by William Lindsay Gresham and stars an ensemble cast including Bradley Cooper, Cate Blanchett, and Toni Collette. Nightmare Alley zeroes in on Stan Carlisle, an ambitious carny who gets embroiled with the dangerous and unpredictable Dr. Lilith Ritter, a corrupt psychiatrist. The film received glowing reviews from audiences and critics alike, especially for its moody, noir atmosphere and del Toro's taut direction, supported by stellar performances from the majority of the cast. Although the raw intrigue of the original novel remains unmatched, Nightmare Alley is a significant departure from the auteur's signature style, with few narrative similarities to The Shape of Water, allowing viewers a glimpse into the strange and perverse aspects of existence from a wholly divergent point of view.

For critics who saw del Toro as a filmmaker of immense potential with his first two exciting, but flawed movies, 2001's The Devil's Backbone was the one that proved he was ready for the big leagues. Set during the final year of the Spanish Civil War—an era del Toro would return to with Pan's Labyrinth—El espinazo del diablo follows a young boy as he arrives at a deeply unsettling orphanage after the death of his father and sets about discovering its dark secrets. While the film is full of some unique scares, what makes The Devil's Backbone stand out is its elegiac portrait of a childhood fractured by war and the sins of the past. There's a tenderness to this ghost story that only makes its traditionally scary aspects more effective. The sight of a young crying ghost boy with his bleeding head cracked like a porcelain vase is one of the most unforgettable images del Toro has ever created.

El laberinto del fauno, released in 2006, felt like the movie that del Toro had been building up to for his entire career. It's the most sublime combination of all of his preferred tropes, set to the backdrop of a deeply tumultuous period in history and told with equal parts poetic fantasy and brutal reality. Oft-described as a more adult Alice in Wonderland, Pan's Labyrinth uses the core of Lewis Carroll's tale as its central hook but is far more interested in exploring the concept of fairy-tales as a parable for the real world's cruelties and abuses.

Young Ofelia's fantasy world straddles the fine line between beauty and grotesque, flipping from one to another on a dime as her real-life during the Spanish Civil War under the iron fist of a violent Francoist general threatens to destroy all she knows. The Pale Man scene remains one of the scariest movie moments of the century so far, made all the more stomach-churning by the fantastical wonders and shocking violence that surrounds it. Guillermo del Toro may make better movies in the future—he certainly has that ability in him—but Pan’s Labyrinth will be extremely hard to topple as the director's greatest work.

No comments: